If you were a general contractor framing a new house or installing kitchen cabinets, the level of measurement reliability described above (+/- 1/16th”) is probably fine. As a result, your reliability (i.e., consistency) is good – maybe even great – but not perfect. Is the distance closer to 5-11/16th inches, or 5-3/4th? Did you start measuring from the inside or outside of the line last time? In this situation, you impose a qualitative interpretation of a tool believed to afford a quantitative result. One reason for this is that your measurement reliability is dependent on your interpretation of what the tool is saying. However, the truth is that each measurement you made wouldn’t be exactly the same as the ones before it. If you were to perform the measurement several times in a row, your results would have relatively high reliability. For example, if you wanted to know the distance between points on a flat surface, you could use a ruler.

In domains such as mechanical engineering, reliability is pretty easy to conceptualize.

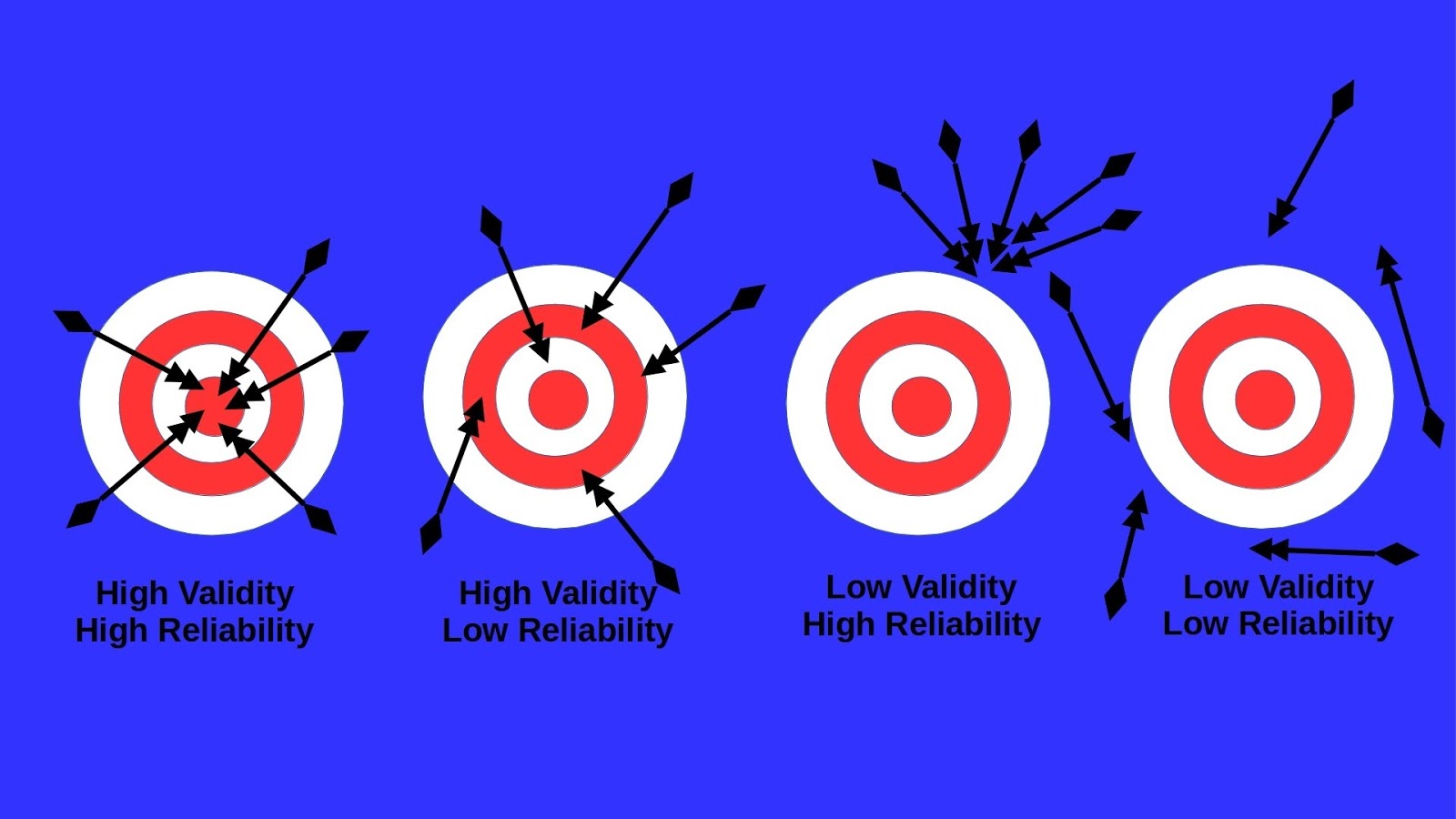

Reliability is the degree to which a specific research method or tool is capable of producing consistent results from one test to the next. To start things off, let’s get on the same page about what we mean by the term, “reliability”. Criterion-Related Validity (Concurrent & Predictive).If you have an example you’d like to share, please talk about it in the comment section below! Jump to: The tricky stuff comes when we examine the different types of validity and reliability, as well as when or why they matter the most.īelow we’ve outlined the basics of validity and reliability as it applies to user-centered research.

It’s not necessarily the difference between them that is so baffling it’s more the fact that there is so much more to it. In research, no two concepts are more confused with one another than validity and reliability.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)